An introductory example

This chapter will walk you through a toy example of what is one of the most obvious uses of Cell, namely as an alternative to an embedded SQL database. It shows some basic features of relational automata, but it's not meant to be a comprehensive introduction to them.

The specific example we'll be using was chosen because it is simple and familiar to anyone but at the same time sophisticated enough to provide a glimpse of the advantages of the functional/relational programming paradigm over OOP. But it is a server application, and Cell is not at the moment a good fit for server software. That's because server applications typically have to handle large amounts of persistent data, something that Cell is not (yet) able to do. With Cell, your entire dataset has to fit in RAM and has to be saved explicitly. It takes only a couple lines of code to load or save it, independently of its size or complexity, but there's currently no support for incremental saving, that is, the ability to save only the part of your dataset that has changed since the last save. There's a way (discussed below) to make sure that unsaved data is never lost, even in the event of a software crash or hardware failure (unless the latter involves a disk failure, of course), but in general these limitations make Cell a better fit for desktop, mobile or embedded applications, which usually have to deal with smaller datasets.

Creating an online forum

In what follows we'll be implementing a small part of the persistent data structures and core logic needed to create an online forum. The forum will consist of any number of chat groups, each of which has a name and an administrator. User will be able to post in the chat groups after they sign up. In order to do so, they'll have to choose a unique username and provide their name and surname and optionally their date of birth. Once they sign up they will be able to join any number of groups, and in each of them they'll have a reddit-style karma, that can go up or down based on the up or down votes from other users. Karma is group-specific: every user may, and generally will, have a different karma in each of the chat groups it has joined. Users will also be able to friend each other, in order to exchange private messages and easily keep track of one another's posts. Friendship is symmetric: if A is a friend of B, then B also has to be a friend of A.

The first thing we'll need to do is to design our application's persistent data structures. In SQL one could create the following set of tables:

CREATE TABLE USERS(

ID INT NOT NULL,

USERNAME VARCHAR(20) NOT NULL,

SIGNUP_DATE DATE NOT NULL,

FIRST_NAME VARCHAR(40) NOT NULL,

LAST_NAME VARCHAR(40) NOT NULL,

DATE_OF_BIRTH DATE,

PRIMARY KEY (ID),

UNIQUE (USERNAME)

);

CREATE TABLE CHAT_GROUPS(

ID INT NOT NULL,

NAME VARCHAR(40) NOT NULL,

ADMIN INT NOT NULL,

PRIMARY KEY (ID),

FOREIGN KEY (ADMIN) REFERENCES USERS(ID)

);

CREATE TABLE MEMBERS(

USER INT NOT NULL,

CHAT_GROUP INT NOT NULL,

JOINED_ON DATE NOT NULL,

KARMA INT NOT NULL,

PRIMARY KEY (USER, GROUP),

FOREIGN KEY (USER) REFERENCES USERS(ID)

FOREIGN KEY (CHAT_GROUP) REFERENCES CHAT_GROUPS(ID)

);

CREATE TABLE FRIENDSHIPS(

USER_1 INT NOT NULL,

USER_2 INT NOT NULL,

SINCE DATETIME NOT NULL,

PRIMARY KEY (USER_1, USER_2),

FOREIGN KEY (USER_1) REFERENCES USERS(ID),

FOREIGN KEY (USER_2) REFERENCES USERS(ID)

);

Note that the USERNAME field in USERS has to be unique and that all fields in all tables are mandatory, with the only exception of DATE_OF_BIRTH in USERS.

In order to create something equivalent in Cell, we'll need to define a relational automaton. At first glance, a relational automaton looks a bit like a class in object-oriented languages: it combines a (mutable) data structure with the code that manipulates it. The similarities end there, though. One of the major differences is that you can make use of relations when defining the (type of the) state of a relational automaton. (The term “relation” is just another name for what in SQL is called a table. For a more formal definition, check the Wikipedia entries for binary and n-ary relations). This is the definition of an automaton that is more or less equivalent, in terms of information content, to the above SQL schema:

type UserId = user_id(Int);

type GroupId = group_id(Int);

schema OnlineForum {

// Unique id generation for users and groups

next_id : Int = 0;

// Users and their attributes

// username must be unique, and date_of_birth is optional

user(UserId)

username : String [unique],

signup_date : Date,

first_name : String,

last_name : String,

date_of_birth? : Date;

// Chat groups and their attributes

chat_group(GroupId)

name : String,

admin : UserId;

// Foreign key integrity constraint. States that

// every group administrator must also be a valid user

admin(_, id) -> user(id);

// Membership relationship between users

// and groups, and its attributes

member(UserId, GroupId)

joined_on : Date,

karma : Int;

// Another foreign key integrity constraint.

// States that the member relation can only

// reference valid users and chat groups

member(u, g) -> user(u), chat_group(g);

// Stores friendship information between user,

// with its only attribute. The relation is

// declared symmetric, the order in which the

// user identifiers are stored doesn't matter

friends(UserId | UserId)

since : Time;

// The friends relation can only reference valid users

friends(u1, u2) -> user(u1), user(u2);

}

User-defined types and entity identifiers

The first thing to notice in the Cell code is the presence of the UserId and GroupId type definitions. In a relational database every entity in the application's domain is usually identified by an integer or sometimes a string while in OOP every entity type is usually mapped to a class that contains all the entity's attributes. In Cell, on the other hand, the recommended approach is to define a custom type like UserId whose sole purpose is to identify an entity of a specific type, but to store all its attributes using relations. Doing so provides a modicum of type safety, makes the code more readable, and most importantly allows us to define functions and methods that are polymorphic on the entity type, just like in OOP, while at the same taking advantage of the benefits provided by relations (more on that later). That's made possible by the fact that in Cell, unlike in SQL, the attributes/columns of a relation can be of any user-defined type.

The UserId and GroupId type definitions may look a bit strange to you if you're not familiar with functional programming: everything is explained in detail in the chapters on data and types, but for now just think of them as records/structs/classes with a single anonymous and public field of type Int.

Entities, attributes and methods

The first line in the body of OnlineForum is the declaration of the member variable next_id, which is just a counter that is read and incremented every time we need to create a new user or chat group id. Nothing new there. The lines that follow are more interesting: they declare the data structures that hold basic information about users:

user(UserId)

username : String [unique],

signup_date : Date,

first_name : String,

last_name : String,

date_of_birth? : Date;

The above declaration makes use of a lot of syntactic sugar. Without it, it would look like this:

user(UserId);

username(UserId, String) [key: 0, key: 1];

signup_date(UserId, Date) [key: 0];

first_name(UserId, String) [key: 0];

last_name(UserId, String) [key: 0];

date_of_birth(UserId, Date) [key: 0];

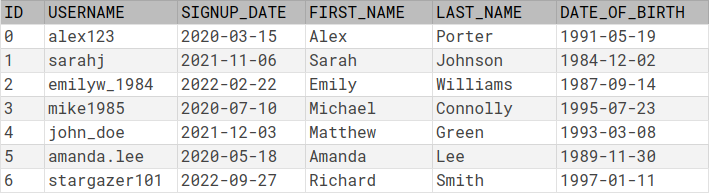

Let's examine the "unsweetened" version first. In the SQL version of the schema, we have a single table that stores all the attributes of a user. In Cell, every attribute is stored in a separate relation. The first relation, user, is a unary relation, that is, a set. It simply contains the identifiers of all registered users. The other five relations, username, signup_date, first_name, last_name and date_of_birth, are binary relations, each of which stores a single attribute of the user entity. That is, while in SQL all the information about a user is stored in a single record of the USERS table as shown here:

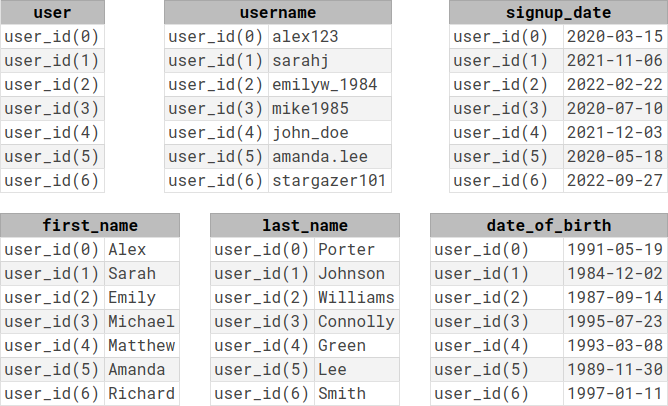

the same data in Cell is split among six different relations:

Note that while in SQL each column/argument of a relation is named, in Cell arguments are only identified by their position.

The reasons for splitting into atomic pieces the information that in an SQL database would be contained in a single record/row will be discussed elsewhere, but one minor benefit is that it makes accessing the attributes of a given entity syntactically more convenient. As an example, this is how you can define a method that generates the complete name of a user by concatenating their first and last name:

using OnlineForum {

String full_name(UserId u) = first_name(u) & " " & last_name(u);

}

The syntax first_name(u) looks exactly like a function or method call, and is not that different from the u.first_name() or u.first_name syntax used in conventional languages, and certainly terser than the SELECT FIRST_NAME FROM USERS WHERE ID = AN_ID used in SQL.

Methods in Cell are just normal functions which are given access to the state of an automaton. They are declared inside a using block, as shown above. Such a block can of course contain any number of methods. Functions and methods in Cell have no side effects, just like in any other pure functional language. They do not modify the state of the program, and they cannot do any I/O: their only purpose is to compute and return a value. The state of an automaton can be mutated, as we'll see later, but any code that does so is kept separate from the rest.

Keys and searches

The [key: 0] in the declaration of signup_date, first_name, last_name and date_of_birth just states that values in the first column of those binary relation have to be unique. In other words, you can only associate a single sign-up date, name, surname or date of birth to each user identifier. An update that violates any of the above integrity constraints is simply aborted, and all the changes it has made to the state of the automaton instance are rolled back, just like in relational databases.

The username relation has two keys, one for each column, which means that not only each person can only have a single username, but also each username has to be unique, that is, it can be associated with only one user.

Being able to declaratively enforce the fact that an attribute cannot have the same value for two different entities is one of the many advantages provided by the relational model. Another, more important one, is that you can efficiently search your dataset on any attribute without having to write any extra code. If you wanted, for instance, to write a method that returns the identifiers of all users who signed up on a given date, you could do it like this:

using OnlineForum {

[UserId] users_who_signed_up_on(Date d) = [u : u <- signup_date(?, d)];

}

The signup_date(?, d) expression iterates (loosely speaking) through all the entries in signup_date whose second argument is equal to d. The first result is produced in constant time, O(1), (it's basically a hashtable lookup) and retrieving each subsequent result is, in terms of efficiency, pretty much like iterating through the elements of a list. Searches can be performed, with the same efficiency, on any attribute of the relation, or any combination of them in the case of ternary relations, which we'll examine later.

Syntactic sugar

Let's now go back to the syntactically sugared version of the schema/automaton. The following declaration:

user(UserId)

username : String [unique],

signup_date : Date,

first_name : String,

last_name : String,

date_of_birth? : Date;

is just a more convenient and concise way of declaring all the unsweetened relations above. The question mark that follows the date_of_birth field qualifies it as optional. You can also declare "multivalued" attributes using the syntactically sugared notation. In the following code, for example:

user(UserId)

... // Same as before

phone_number* : String;

the phone_number attribute can have any number of values (including zero). That's rewritten by the compiler into a binary relation with no keys, which can have multiple entries for the same UserId value:

phone_number(UserId, String);

You can also tag an attribute with a + sign, which marks it as a mandatory multivalued attribute, that is, one that must have at least one value, and can have more than one.

user(UserId)

...

phone_number+ : String;

There's actually more going on with the syntactically sugared notation, but we won't go into detail here.

Foreign keys

The next section in the definition of OnlineForum is the declaration of the data structures/relations that hold the information about chat groups. It's very similar to what we've seen before. What's new, though, is the line that follows:

admin(_, id) -> user(id);

That's a foreign key declaration, and it states that every chat group administrator must be a valid user, or in other words, that every value in the right column of admin must also be an element of user. Scrolling down a bit, you'll find the declarations of another two foreign keys, whose meaning should be obvious: in order for user u to be a member of chat group g, u and g must be valid user and chat group identifiers respectively, and for users u1 and u2 to be online friends, both u1 and u2 must be valid user ids:

member(u, g) -> user(u), chat_group(g);

friends(u1, u2) -> user(u1), user(u2);

Relationships and their attributes

The next set of relations store the information on which chat groups each user has joined:

member(UserId, GroupId)

joined_on : Date,

karma : Int;

As you would expect, that's only syntactic sugar for the following relations:

// User #0 is a member of chat group #1

member(UserId, GroupId);

// User #0 joined chat group #1 on #2

joined_on(UserId, GroupId, Date) [key: 0:1];

// User #0 has karma #2 in chat group #1

karma(UserId, GroupId, Date) [key: 0:1];

The comment that precedes the declaration of each relation is the informal relation predicate, that is, the informal meaning of each entry in the relation, with #0, #1 and #2 being the placeholders for the first, second and third argument of the relation respectively.

Each entry in the binary relation member encodes what in an E/R model would be called a relationship between two entities, namely the fact that a specific user has joined a specific chat group. It's a many-to-many relationship, with every user being able to join any number of groups, and groups having any number of members. Just like attribute relations like name or date_of_birth it can be searched efficiently on any attribute: if, for example, u the id of a user and g that of a chat group (of type UserId and GroupId respectively), then the expression member(u, ?) will (loosely speaking) iterate through the ids of all chat groups u has joined, and member(?, g) will provide the list of members of group g.

The two ternary relations joined_on and karma store what we can regard as attributes of the membership relationship, as opposed to attributes of entities like users or groups. The first two arguments form a key for both relations, meaning that for each combination of user and group there can be only one join date and one karma, but a user can still, for instance, have a karma in one group and a different one in another. The fact that attributes like these cannot be "attached" to any single entity makes them awkward to model in conventional languages, which use records as their primary composite data structure, but can be represented very elegantly using relations. Accessing the value of one such attribute is very similar to accessing the attributes of an entity, like username or admin: the expression karma(u, g) returns the karma of user u in group g (and of course will fail if u never joined g). Similarly, ternary relations can be searched on any argument or combination thereof: joined_on(?, g, d), for instance, will produce a list of all users who joined group g on day d. Lookups are performed in constant time (O(1)), and the same goes for retrieving the first result in any search.

Symmetric relations

Finally, we have the friends relation and its only attribute, since:

friends(UserId | UserId)

since : Time;

This is how it would look without syntactic sugar:

// Users #0 and #1 are online friends

friends(UserId | UserId);

// Users #0 and #1 have been online friends since #2

since(UserId | UserId, Time);

friends look similar to member, with the only difference being that its two arguments are separated by a vertical bar instead of a comma, which tells the compiler that the friends relation is symmetric. Without that, the fact that users u1 and u2 are online friends could be recorded as either the u1, u2 or u2, u1 entry inside friends, or even both of them. That would of course be a problem, because it would force us to account for both possibilities when checking if two users are friends or when deleting such fact from the dataset, thereby making our code more complex and error prone than it needs to be. The problem would be even worse for the since relation, as it could end up with two conflicting facts inside it: u1, u2, t1 and u2, u1, t2. By declaring the arguments of friends and the first two arguments of since symmetric, all these issues will be automatically deal with by the compiler whenever we read the dataset, and insert, update or delete the data in it.

Messages and message handlers

Now that we've completed the design of our data structures, it's time to start writing some actual code. We've already written a couple of read-only methods:

using OnlineForum {

String full_name(UserId u) = first_name(u) & " " & last_name(u);

[UserId] users_who_signed_up_on(Date d) = [u : u <- signup_date(?, d)];

}

but code that mutates the state of an automaton is quite different. The only way to mutate the state of a relational automaton is by sending it a message. A message is just a value, that is, a piece of data. For every type of message an automaton can accept there's a corresponding message handler that is invoked when such a message is received. The message handler is where the actual updating of the state of the automaton instance takes place.

Let's start by defining the message and message handler pairs that add a new user to the dataset:

type AddUser = add_user(

id: UserId,

username: String,

signup_date: Date,

first_name: String,

last_name: String,

date_of_birth: Date?

);

OnlineForum.AddUser {

id = this.id;

// Inserting the new user id

insert user(id);

// Setting all the mandatory attributes

insert username(id, this.username);

insert first_name(id, this.first_name);

insert last_name(id, this.last_name);

insert signup_date(id, this.signup_date);

// Setting the (optional) date_of_birth attribute, if available

if this.date_of_birth?

insert date_of_birth(id, this.date_of_birth);

}

The first declarations defines the type of the message, which is basically just a record containing all the information about a new user. The date_of_birth field is optional. The second declaration defines the message handler, which is pretty straightforward, just a bunch of insert statements, one of which is conditional since date_of_birth is optional. The only thing to note is the this keyword that is used to access the value of the message. There's also some syntactic sugar for the insert statement. The above message handler can be rewritten more tersely as follows:

OnlineForum.AddUser {

insert user(this.id)

username = this.username,

first_name = this.first_name,

last_name = this.last_name,

signup_date = this.signup_date,

date_of_birth = this.date_of_birth if this.date_of_birth?;

}

Adding new chat groups, memberships and friendships is very similar to adding users, so we can skip over that part. A more interesting message handler is the one that deletes a user from the dataset, since its logic is a bit more sophisticated: if the user is the administrator of one or more chat groups, we'll have to pick a new administrator for them. We'll pseudo-randomly choose one of the members with the highest karma, or just delete the group if there's no one left. Here's the code:

OnlineForum.delete_user(id: UserId) {

id = this.id;

// Deleting a user's data, memberships and friendships

// All attributes are deleted automatically when the

// corresponding entity or relationship is deleted

delete user(id), member(id, *), friends(id, *);

// If the user is the administrator of one or more chat groups,

// we need to choose a new administrator for them, or delete

// them altogether, if there's nobody left

for g <- admin(?, id) {

members = [u : u <- member(?, g), u != id];

if members != [] {

// The new administrator is randomly chosen

// among all members with the highest karma

new_admin = any(max_by(members, karma($, g)));

update admin(g, new_admin);

}

else

// No members left, deleting the group

delete chat_group(g);

}

}

Here we've used a bit of syntactic sugar to avoid an explicit type definition like the type AddUser = ... we saw previously. The following definition:

OnlineForum.delete_user(id: UserId) {

...

}

is the same as:

type DeleteUser = delete_user(id: UserId);

OnlineForum.DeleteUser {

...

}

save for the fact that type of the message is not explicitly named (how exactly this works will become clear after reading the chapter on types).

Differences between relational automata and classes

We mentioned at the beginning of this chapter that relational automata have some superficial similarities with classes in OOP, in that they combine a mutable data structure with the code that manipulates it, but that the similarities end there. It's now time to elaborate a bit on that.

The first difference is that, as we've already seen, the state of an automaton is defined using the relational model. That's a very major difference, which we'll be discussing elsewhere in the documentation.

Second, there's a strict separation between (pure) computation and state updates. Methods can only compute and return values, but do not modify the state of an automaton. Message handlers, on the other hand, can change the state of the automaton, but do not return a value. Keeping computation and updates separate provides many of the benefits of functional programming, while avoiding the difficulties that the latter paradigm has in dealing with state.

Moreover, message handlers are limited in what they can do: they can only modify the state of the automaton instance that receives the message. They cannot do any I/O, and they cannot alter the states of other automata. That means, among other things, that different automaton instances can be safely updated concurrently by different threads, since they do not share mutable state.

Third, all updates are run inside a transaction. If, for whatever reason, an update fails, the message that triggered it is simply discarded and the state of the automaton is left untouched. That provides a very robust error handling mechanism.

Fourth, the behavior of an automaton is deterministic: the state of an automaton instance after a message has been processed depends only on the previous state and the message itself. Combined with the fact that updates can only be triggered by messages, which are just values that can be manipulated and stored like any other piece of data, that means that is very easy to exactly reproduce the entire execution of an automaton, if one takes care to save all messages that are sent to it. If you create another instance of the same automaton type, with the same initial state, and send it the same sequence of messages, you'll reproduce the exact behavior of the original automaton.

That's of course very useful during debugging, because it means that you can reproduce any bug with a minimal effort. It's also handy when refactoring your code, because you can send the same sequence of messages to both the old and the new code, and compare their behavior. You can basically get a lot of regression tests for free.

Automata also support orthogonal persistence. One can, at any time, take a snapshot of the state of an automaton, which can then be saved to persistent storage. Such snapshot can later be used to recreate an identical copy of the original automaton, which will just pick up where the original instance left off. We'll see how to do it in the next paragraphs.

As already mention, the state of an automaton has to be saved explicitly, and there's no way at the moment to save only the part of the state that has changed since the last save. But if you keep a log of the messages received by an automaton, you'll only need to save its state once in a while, without running the risk of losing data: if a crash occurs when your application has some unsaved data, all you need to do is start from the last saved state and resend all messages that were received after that, and you'll recreate the exact state you lost in the crash.

There are also other, more interesting ways to take advantage of the fact that updates are deterministic and message-based, when building distributed applications, but we won't discuss them here.

Interfacing with Java

While it is possible to build a complete application with it, Cell is designed to be a domain-specific language, used to generate code for a number of different target languages. The ones that are already supported are Java and C#. We'll be using the Java code generator here, but the differences between the two are minimal anyway. When compiling the code that we've seen in this chapter, the code generator will produce an OnlineForum class that can be used from your native Java code to instantiate, control and read the state of the instances of the automaton defined in the Cell codebase. Here's the interface of the generated Java class, in pseudo-Java code:

package net.cell_lang;

class OnlineForum {

OnlineForum();

void load(Reader writer);

void save(Writer reader);

void execute(String);

void addUser(

long id,

String username,

LocalDate signupDate,

String firstName,

String lastName,

LocalDate dateOfBirth

);

void deleteUser(long id);

String fullName(long u);

long[] usersWhoSignedUpOn(LocalDate d);

}

Let's start with the pair of complementary methods load(..) and save(..). The latter save a snapshot of the state of the automaton to a java.io.Writer object. The state of the automaton is saved in Cell's standard textual format, so that is can be manually inspected and modified. The load(..) method, on the other hand, erases the current state of the automaton and loads a new state from the provided java.io.Reader, as long as that's a valid state for the automaton in question. The new state must be in the same text format used by the save(..) method. If the load operation fails, for whatever reason, the state of the automaton is left unchanged. Loading a previously saved state results in an identical copy of the original automaton, that will pick up where the original left off, and behave in the exact same way.

The next method, execute(..), can be used to send a message to the automaton. The message is provided as a string containing its standard textual representation. If an error occurs during the execution of the message handler an exception is thrown, and the state of the automaton is left unchanged, as already mentioned. This is not the only way to send the automaton a message, as there's a much faster alternative that we'll see in a minute, but having a generic way to send any message in textual form comes in handy in many situations.

Here's an example of how to use the three methods just discussed. The following Java code creates an instance of OnlineForum, loads an initial state for it from a file, sends a message to the automaton to delete one specific user from the dataset and saves the resulting state/dataset to another file:

// Creating an instance of OnlineForum

OnlineForum onlineForum = new OnlineForum();

// Loading the initial state from a file

try (FileReader reader = new FileReader("initial-state.txt")) {

onlineForum.load(reader);

}

// Sending a message

onlineForum.execute("delete_user(id: user_id(5))");

// An equivalent but faster way of sending the exact same message

// onlineForum.delete_user(5);

// Writing the new state to a file

try (FileWriter writer = new FileWriter("final-state.txt")) {

onlineForum.save(writer);

}

Here's an example of what a valid state for the OnlineForum automaton looks like, once it's converted into its standard textual representation.

All the remaining methods are specific to each type of automaton, and they're used to invoke its message handlers and methods. In this specific case, void addUser(..) and void deleteUser(long) can be used to send the corresponding messages, and in many cases they should be preferred to execute(..) since they're much faster, while string fullName(long) and long usersWhoSignedUpOn(Date) invoke the corresponding (read-only) methods.

The only thing left to mention is the fact that, in order for the generated code to interface smoothly with hand-written Java code, the Cell compiler tries to map each Cell type that appears in the interface of an automaton to a standard Java type or to generate a corresponding Java class for it: in the rare cases in which that fails, the corresponding piece of data is returned or has to be passed in as a string containing the textual representation of the Cell value. The details of the mapping are described in another chapter.

Inheritance hierarchies and polymorphism

Before we wrap up this introduction, let's take a look at how inheritance hierarchies can be modeled in Cell. As an example, let's say we've to build a very simple payroll system for a company that pays its employees on a weekly basis. Employees are of four types: salaried employees are paid a fixed weekly salary regardless of the number of hours worked, hourly employees are paid by the hour and receive overtime pay (i.e., 1.5 times their hourly salary rate) for all hours worked in excess of 40 hours, commission employees are paid a percentage of their sales and base-salaried commission employees receive a base salary plus a percentage of their sales.

The first step is to create typed identifiers for each of the four types of employees:

type SalariedEmployee = salaried_employee(Int);

type HourlyEmployee = hourly_employee(Int);

type CommissionEmployee = commission_employee(Int);

type BasePlusEmployee = base_plus_employee(Int);

The type definitions above are very similar to UserId and GroupId we saw previously (we just dropped the "Id"/"_id" suffixes). Now we can define the type of all employees:

type Employee = SalariedEmployee,

HourlyEmployee,

CommissionEmployee,

BasePlusEmployee;

Employee is just the union of all employee types, in the sense that every value that belongs to one of the four basic types of employees also belongs to Employee (types in Cell have set semantics). It's also useful to define the type of all employees that earn commissions:

type AnyCommissionEmployee = CommissionEmployee, BasePlusEmployee;

AnyCommissionEmployee is obviously a subset/subtype of Employee, and the compiler recognizes it as such. The following Workforce schema stores basic information about employees:

schema Workforce {

// Next unused employee id

next_employee_id : Int = 0;

// Shared attributes of all employees

employee(Employee)

first_name : String,

last_name : String,

ssn : String;

// Attributes of salaried employees

employee(SalariedEmployee)

weekly_salary : Money;

// Attributes of hourly employees

employee(HourlyEmployee)

hourly_wage : Money,

hours_worked : Float;

// Attributes of all employees that earn commissions,

// including those with base salary + commissions

employee(AnyCommissionEmployee)

gross_sales : Money,

commission_rate : Float;

// Attributes of employees with base salary + commissions

employee(BasePlusEmployee)

base_salary : Money;

}

The unary relation employee contains the identifiers of all employees in the system. The first set of attributes, first_name, last_name and ssn, are common to all types of employees, while others apply only to a specific type: weekly_salary is only for salaried employees, hourly_wage only for hourly employees, and so on. Finally there's a couple of attributes, gross_sales and commission_rate, that are shared by all types of employees that can earn commissions.

Now we can define the polymorphic earnings(..) method, which is implemented differently for each type of employee:

using Workforce {

Money earnings(SalariedEmployee e) = weekly_salary(e);

Money earnings(HourlyEmployee e) {

hours = hours_worked(e);

wage = hourly_wage(e);

earnings = hours * wage;

earnings = earnings + 0.5 * (hours - 40.0) * wage if hours > 40.0;

return earnings;

}

Money earnings(CommissionEmployee e) =

commission_rate(e) * gross_sales(e);

Money earnings(BasePlusEmployee e) =

base_salary(e) + commission_rate(e) * gross_sales(e);

}

This example is discussed in more depth in another chapter.

Where to go from here

It's interesting at this point to implement the data structures and logic of the online forum example in both Cell and Java, in order to see how the two paradigms (functional/relational programming and OOP) compare. You can read about it here.

The relational automata section contains the complete documentation for relational automata, but you'll have to read about data and types first. The overview will give you some additional high-level information.

This chapter focused on the most important of the two types of automata, namely relational automata. For an overview of the other type, reactive automata, just head to the corresponding chapter. It should be readable even without any previous knowledge of the language.